Onsen is a Japanese term for natural hot springs. The term comes from the kanji characters 温泉, which literally translates to “warm spring.”

When someone tells you they want to experience the onsen culture in Japan, they are referring to bathing in the hot springs, while usually staying at a ryokan. You will find that there are countless onsen areas in Japan, and many of them have small towns surrounding the natural waters.

While many countries around the world are blessed by natural thermal waters, Japan created rituals around bathing in hot springs. The history is as interesting as it is culturally rich.

Ancient Origins and Mythological Significance

The use of hot springs in Japan dates back to prehistoric times. Archaeological evidence from shell mounds indicates that the indigenous people of Japan used natural hot springs for bathing and heating from as early as the Jomon period (14,000-300 BCE). Onsen are mentioned in the oldest Japanese texts, including the “Nihon Shoki” (Chronicles of Japan, 720 AD), which tells of emperors and other notable figures using onsen for healing and spiritual purification.

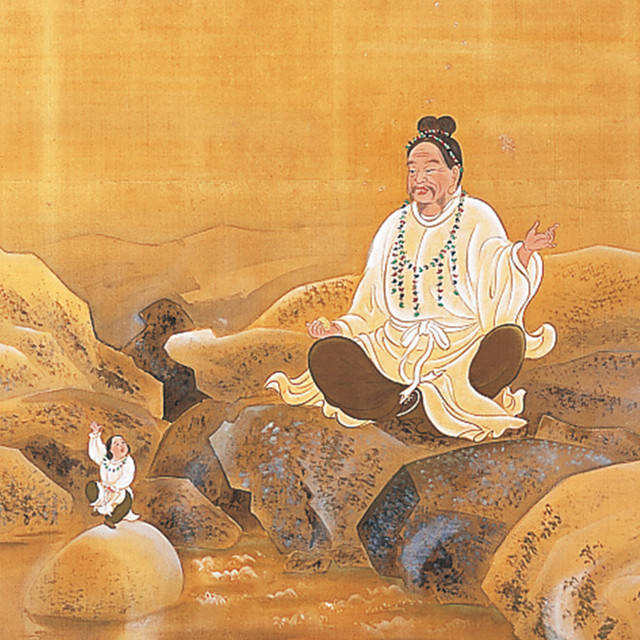

Onsen also appear in Japanese mythology. For example, the deity Ōkuninushi (mentioned in the Kojiki or the Japanese Records of Ancient Matters) is said to have healed his wounds in an onsen after a particularly brutal encounter, establishing a divine connection between onsen and healing.

Heian Period to Kamakura Period (794-1333)

During the Heian period (794-1185), onsen began to be recognized by the Japanese court for their therapeutic properties. Nobles and samurai would travel to hot springs for healing and rejuvenation. The Kamakura period (1185-1333) saw the rise of warrior classes, and onsen continued to serve as retreats for rest and healing for these warriors.

Edo Period (1603-1868) – The Golden Age of Onsen

The Edo period marked a significant turning point for onsen culture due to the peace and stability under the Tokugawa shogunate. This era witnessed a surge in travel and tourism as part of the “sankin-kōtai” policy, which required feudal lords (daimyo) to travel regularly to Edo (modern-day Tokyo). Daimyo were required to maintain residences both in their home domains and in Edo. They had to live in Edo for one year and could return to their provinces for the next. This effectively kept them financially burdened by the need to maintain two households and limited their ability to plot against the shogunate due to their frequent absences from their power bases.

As daimyo and their processions traveled across the country, they would often stop in onsen towns to rest and rejuvenate. This regular influx of high-status visitors and their followers provided a significant economic boost to these towns. Local inns, ryokans (traditional Japanese inns), and other businesses thrived by catering to these travelers, enhancing local economies.

To accommodate the needs of daimyo processions, roads improved and the infrastructure of onsen towns was often enhanced. The presence of daimyo and their retainers helped to spread the culture of onsen bathing across Japan. As these elite groups often sought the health and relaxation benefits of hot springs, onsen culture became more widely known and appreciated throughout Japanese society.

Some of the most famous onsen towns include Hakone, Beppu, and Noboribetsu.

Meiji Era (1868-1912) and Beyond

The Meiji Restoration brought about profound changes in Japanese society, including increased exposure to Western ideas and technologies. Onsen adapted to these changes; they began to modernize with the introduction of more sophisticated facilities while maintaining traditional aspects.

During the 20th century, particularly after World War II, onsen experienced a resurgence as domestic tourism boomed in Japan. The Japanese government promoted onsen as part of Japan’s cultural heritage and tourism industry, leading to further development of onsen towns.

Contemporary Onsen Culture

Today, onsen remain a cherished part of Japanese culture. They are celebrated not only for their health benefits, but also as places to meet and relax.

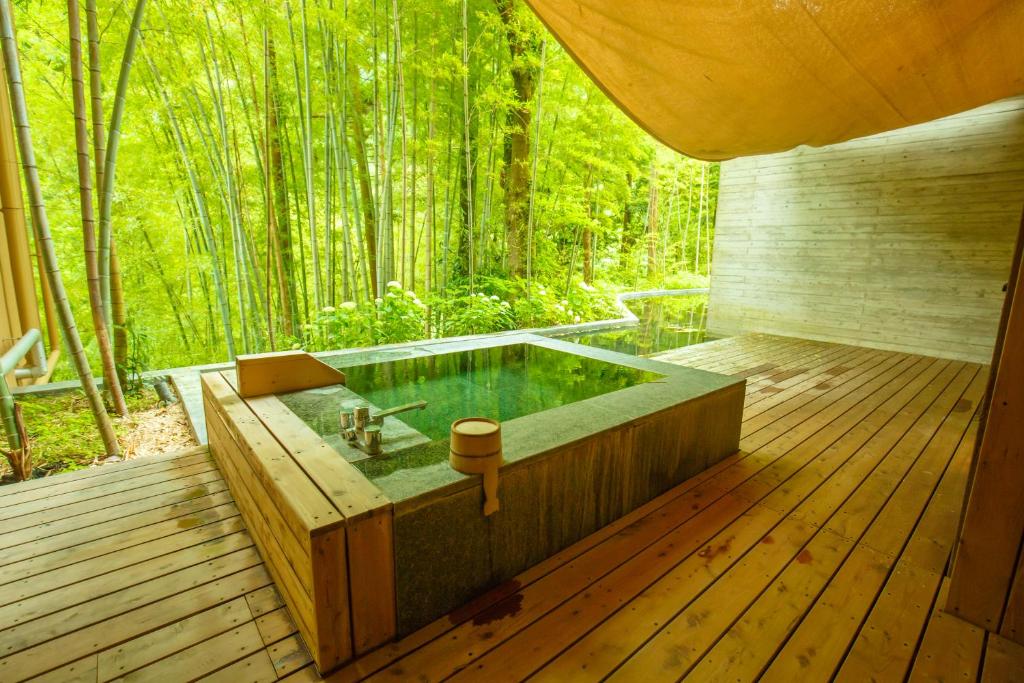

With over 27,000 hot spring sources, contemporary onsen vary widely from traditional settings in ryokans (Japanese inns) to modern spa resorts. The water in onsen must be at least 25°C and contain one or more of 19 designated beneficial minerals to be classified officially as an onsen.

Despite modern innovations, many onsen still adhere to traditional practices, such as gender-segregated bathing and the prohibition of swimsuits to maintain the purity of the water.

Tattoos are still considered taboo in onsen environments and those who have many tattoos on their body, are usually prohibited from using a public onsen. Luckily, many places now offer private onsen or have tattoo friendly onsen, so everyone can enjoy them. This is especially difficult for Western tourists who see tattoos as a form of self-expression and not something associated with criminal gangs, like in Japan.

Cultural Legacy

Onsen towns often strive to maintain a balance between development and preserving the natural beauty and integrity of the hot springs. Onsen contribute significantly to local economies, supporting hospitality jobs and related services, in otherwise very rural areas.

The cultural legacy of onsen is profound. They represent Japan’s deep connection to nature, the essence of Japanese hospitality, and a sanctuary for physical and spiritual well-being.

Onsen serve as a communal space for relaxation and social interaction, free from the hierarchies and formalities typical of other aspects of Japanese life.

The practice of “hadaka no tsukiai,” or naked socialization, in onsen is believed to foster a sense of equality and openness among bathers, as it eliminates social distinctions and clothing. The traditional practice of naked bathing is thought to foster a sense of equality among bathers because everyone is equally exposed and vulnerable.

The other reason people bathe naked in onsen, besides the practical aspect of cleanliness, is deeply rooted in Japanese etiquette and the cultural emphasis on purity. Clothing is thought to contaminate the pure waters of the hot spring.

Onsen and international tourism

Onsen have long been a magnet for international tourists seeking a unique and authentic Japanese experience.

Bathing in an onsen is not just about relaxation, but also about understanding and participating in a longstanding Japanese custom. Many onsen facilities are located within ryokans, which provide a cultural experience that includes tatami floors, futon beds, yukata robes, and traditional Japanese meals.

Onsen play a significant role in Japan’s tourism industry, appealing to foreigners through their blend of cultural authenticity, health benefits, and natural beauty. The experience of visiting an onsen is not just about the bath itself but about enjoying a holistic cultural and wellness experience that is quintessentially Japanese.